About the Author and the Site

First, a note of thanks to those who have, over the last quarter of a century, been extremely generous in helping me build and sustain this record of writing on art and faith.

Above all, thanks to Laure Hittle and Carl-Eric Tangen, whose support, which has taken very different forms, has been the fuel that has kept the flame burning.

I’m also deeply grateful to Chris Angus, Benjamin Bronsink, Winston Chow, Kimberly Fisher, Timothy Grant, Cynda Pierce, and Julie Silander

Soon, I will post a link to a page we will call “The Credits,” where I’ll thank a cast and crew who have made this all possible.

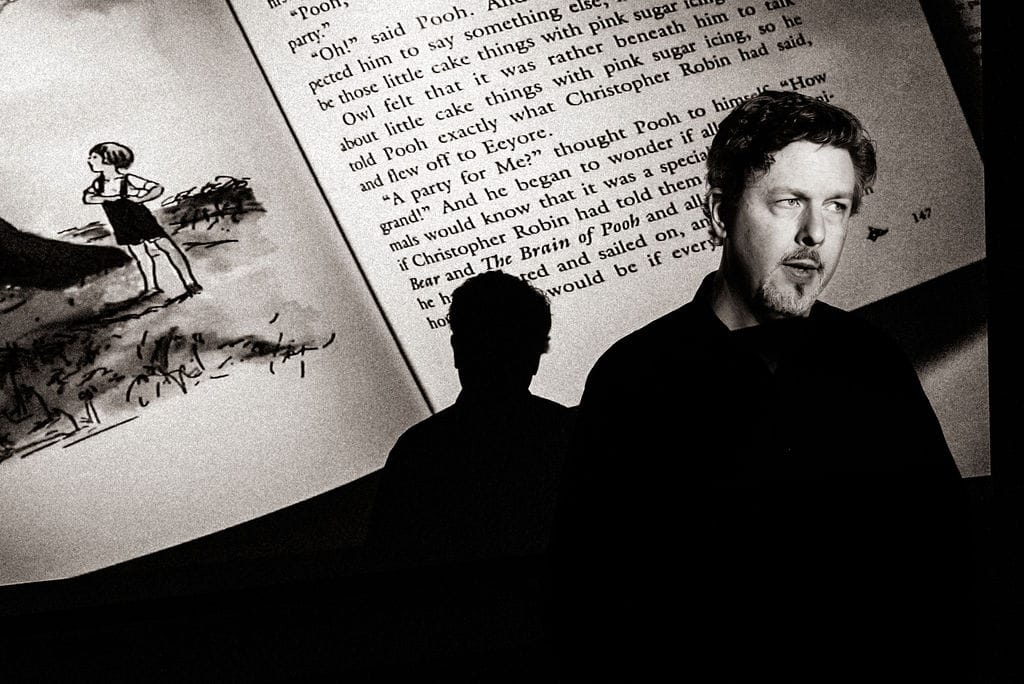

My name is Jeffrey Overstreet,

and I'm inviting you into experiences

at the intersection of art and faith* —

as audiences, as students, as fans, and as artists.

For decades, my website was called Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet. Then I started a journal at Substack called Give Me Some Light. I am in the process of merging those sites into a bigger, better site here at Ghost — and now it's time for me to repurpose those old titles and make my name the banner for the whole endeavor. The film branch of the site will be called Looking Closer, the music branch Listening Closer, and the personal journal Give Me Some Light.

I'm here as an artist first — that is, I'm a fiction writer with a passion for poetry. (And that extends to my marriage—I've been married to my favorite poet and editor for almost 30 years now.) I have loved writing stories since I was about five years old. Perhaps you've discovered my novels: Auralia's Colors, Cyndere's Midnight, Raven's Ladder, and The Ale Boy's Feast, all published by WaterBrook Multnomah, an imprint of Random House. I'm hard at work on new stories, and it is my intention to develop a new branch of this website soon that will feature short and serialized fiction.

As a lover of the arts, I'm here as a critic second — not to find fault with art, but to celebrate beauty, truth, and excellence where I find it; to engage with others in conversation about it; and to grow in my exercise of discernment.

And I am also here as an educator. For the last decade, I have taught courses on creative writing, film, literature, and academic writing at Seattle Pacific University. Today, I am a tenured associate professor of English and writing there. In 2024, the students of Seattle Pacific University cast their votes, and they honored me with the Undergraduate Professor of the Year award—perhaps the most surprising and meaningful affirmation I have ever received. But I have looked at all of my work, even the writing I did as a high school student, as a form of teaching.

"How can I subscribe? And why should I?"

On this site, you’ll find my reflections, reviews, recordings, videos, and links that will, I hope, enhance your own engagement with the overlapping worlds of art and faith.

Sign up for a free subscription, and you’ll receive in your email inbox various posts that I've made free and accessible for everyone.

Sign up for a paid subscription, and you’ll have full access to all the posts, including my exclusive First Impressions posts with my initial thoughts about new movies and more. You'll discover new movies, and you'll read new perspectives that enrich your appreciation of old favorites. You'll find new music you might otherwise have missed, and you'll learn about why I'm inspired and moved by it. You won’t have to worry about missing anything I publish. Every new post goes directly to your inbox. Paid subscriptions make my work possible — they cover the costs of sustaining this website, and they pay for my access to all kinds of art: movies, music, literature, and more. I am ever so grateful to anyone who demonstrates that they value this work with contributions large and small.

“Anybody can blog. Show us your credentials.”

As I mentioned above, I've been writing since I learned how to write as a young child. While I have several books that you can find through any good bookstore, those are just a few examples of my work. I've been writing for readers online since the late ’90s.

I wrote routinely about movies for Christianity Today over a decade and eventually got a “senior film critic” badge (which means I’m old, I guess). After a decade of writing for them, I posted over one hundred mini-essays about film at ImageJournal.org. I was surprised to find my work noted TIME and The New Yorker. For a few years I wrote for Paste, and I’ve also been published in/at Comment, Relevant, Christ and Pop Culture, and — much to my delight — the great film-essay site Bright Wall Dark Room.

At the beginning of my book Lost & Found in the Cathedral of Cinema, I dedicate the book to the memory of the MFA in Creative Writing program at Seattle Pacific University. I had already visited the program as a speaker on creative nonfiction, due to my many years of work as a film critic and essayist. But I so admired what SPU was providing there—a near-miraculous program and community that merged artistic excellence with a profound vision of faith—that I knew I would grow and learn there. My wife Anne and I both earned our MFAs there from 2014–2016. I was mentored there by authors Paula Huston and Lauren Winner, and learned so much from other great writers on the faculty: Robert Clark, Gina Ochsner, Jeanine Hathaway, and Jeanne Murray Walker. In a lifetime of learning in Christian education, the MFA in Creative Writing at SPU was the most meaningful in developing both my creativity and my faith, before the program's tragic closure by administrators who did not understand or appreciate what a bright light it was in the worlds of art and faith.

Since then, I have been teaching courses on creative writing, film interpretation, literature, and acaedmic writing. I've taught courses, led seminars, mentored students in independent studies, and spoken at universities, colleges, high schools, home-schooling programs, arts retreats, churches, and more for more than 20 years.

"You have a vast reservoir of archives here. Where did all of this come from?"

I've been writing reviews since the mid ’90s, and I'm working on making the best of my writing from the past several decades available here.

That means I'm consolidating my enormous archive of reviews and reflections from my original blog, Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet, and all that I published in a few years on Substack.

You'll also find a great deal of work that was published elsewhere, in journals such as Image, Paste Magazine, Response Magazine, Christianity Today, and more.

“I demand references, Overstreet. Where can I find some reassurances about your writing?”

Well, here are a few who have offered some kind words without any bribery:

Matt Zoller Seitz — editor of RogerEbert.com, author of The Wes Anderson Collection, founder of the film review websites The House Next Door and Press Play (at indieWire), and television critic for New York Magazine — on Overstreet’s film writing:

Jeffrey is … one of my favorite film critics. He writes with great lucidity and compassion about all sorts of movies, from all sorts of angles, but what I value most about his work is the theological-moral perspective he takes on things. He’s not a dogmatic scold, sifting through popular art looking for work that fits a rigid world view; he’s more interested in Looking Closer, as his blog title suggests, to discover what, if anything, the work is saying.

Scott Derrickson — writer and director, Doctor Strange, Sinister, The Exorcism of Emily Rose — on Through a Screen Darkly:

Jeffrey Overstreet is a spiritual bloodhound, rabidly tracking the voice of God through his own experience of the history of cinema. In Through a Screen Darkly, he leads the way for all of us, demonstrating how we can look closer and experience the divine invasion of film for ourselves.

Eugene Peterson — author of The Message, The Pastor, and Eat This Book — on Overstreet’s moviegoing memoir Through a Screen Darkly:

Jeffrey Overstreet is a witness. While habituating the dark caves of movie theaters, he gives articulate witness to what I too often miss in those caves — the contours of God’s creation and the language of Christ’s salvation. … I find him a delightful and most percipient companion — a faithful Christian witness.

Dick Staub, author of The Culturally Savvy Christian — on Through a Screen Darkly:

… [T]he spirit of the Inklings is alive and well and at least one living writer could have held his own at their table!

Image journal on Overstreet’s work:

Jeffrey Overstreet is a trespasser. He’s constantly moving outside of the borders of what church and culture deem to be ironclad, eternal categories (sacred vs. profane, high culture vs. popular culture) — and he has a knack for bringing people along with him. His passport? The imagination. In his writing on film, he has used the mighty megaphone of Christianity Today to challenge its readers to take a more mature, holistic approach to film. His film criticism doesn’t count swear words or anatomical parts; rather, it speaks of beauty, paradox, and what it means to be human. Overstreet has pursued this vocation with such integrity and forcefulness that the secular media have picked up on it — precisely because he dares to trespass against the arbitrary categories of what is deemed ‘religious’ and what is considered ‘public.’ He brings this spirit of freedom to all that he does, from his many illuminating posts on various online message boards to his writing for Seattle Pacific University’s publications to his newest venture: fantasy novels. Even there he’s crossing boundaries, bringing a more literary sensibility to a genre that’s often mere swords and sorcery. When you trespass with Jeffrey Overstreet, you don’t have to ask for forgiveness.

Darren Aronofsky — director of Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain — in a message to the author about Through a Screen Darkly (shared with permission):

Inspirational…. Sometimes all of us forget that love for movies, that internal spark inside us that movies lit, and your book is going to remind many of us about it.

Steven D. Greydanus — film critic for Christianity Today, Crux, and The National Catholic Register — on Through a Screen Darkly:

[Overstreet] doesn’t just tell you whether or not he liked a movie. He offers you a seat next to him as the movie unfolds and he points out and reflects on the things that thrill, fascinate or trouble him. It’s an invitation not only to look more closely, but to ponder more deeply and appreciate more fully.

Gregory Wolfe — publisher and editor of Image; author of Beauty Will Save the World and Intruding Upon the Timeless: Meditations on Art, Faith and Mystery — on Through a Screen Darkly:

Through a Screen Darkly constitutes a milestone in Christian reflection about contemporary film. This is not simply because it is full of insightful analysis and a generous, open spirit, but because its vision grows out of a passionate, personal journey. This is film criticism with a soul and a sense of urgency growing out of the conviction that faith and the imagination need one another — the better to open our eyes to the flickerings of God’s grace.

Robert Clark — Edgar-Award-Winning Author of Mr. White’s Confession and Washington Book Award-Winning Author of Dark Water — on Through a Screen Darkly:

In this beautiful and incisive meditation on the art of film — at once memoir, manifesto and critical guide — Jeffrey Overstreet teaches us not only why film should matter to people of faith but how to see movies as vehicles for inspiration and, indeed, grace.

Brett McCracken — writer and reviewer for Relevant Magazine and Christianity Today — on Through a Screen Darkly:

If you propose in academic or professional film circles the notion of ‘Christian film criticism’ as a serious discipline … you will probably be laughed off. Thankfully, we are taking steps to change that. A significant step in the right direction has come with the brand new book by Jeffrey Overstreet, Through a Screen Darkly…. Overstreet … has taken it upon himself to free Christian arts journalism from the ghetto and shackles of narrow-mindedness, utilitarianism and aesthetic ambivalence (as well as the flipside — aesthetic gluttony). His new book [Through a Screen Darkly]… gives hope to all of us who struggle for a more thoughtful, measured and empathetic Christian perspective toward cinema.

Dr. David Frisbie — writer at the award-winning Armchair Interviews site — on Through a Screen Darkly:

Scarcely a few decades ago, the phrase ‘Christian movie reviewer’ might have seemed an oxymoron: entire denominations and churches shunned the theatre, believing it to be evil per se. Overstreet is a much-needed voice that helps postmodern Christians and others be fully engaged with their culture, yet move beyond its limitations to produce high-quality films.

Mark Moring — former editor of ChristianityTodayMovies.com — on Through a Screen Darkly:

Jeffrey Overstreet has taught me a great deal not just about how to watch movies, but also how to glean truth, beauty and redemption from films of all types — even those that aren’t necessarily comfortable to watch. I am learning the art of looking closer, and this book takes that art — and that education — to even deeper, and thus more rewarding, levels.

I invite you to join me in the richly rewarding exercise of looking and listening closer: to movies, music, literature — to all kinds of art. This opens up opportunities for us to attend more closely to each other, to the world around us, and to our own mysterious hearts.

Don’t worry: It’s not as complicated as it sounds. It’s a way of enjoying everything from Tchaikovsky to Taylor Swift, from The Seventh Seal to Star Wars, from The Brothers Karamazov to Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

The rewards don’t come from me: I’m just inviting you to experience them with me. The rewards — surprise, revelation, joy, transformation — come from our encounters with beautiful, mysterious, and truth in art. What’s more: As we attend to art, gleaning meaning from it with the “ears of our ears” and the “eyes of our eyes,” the more we will learn to glean meaning from our lives.

I exercise the muscles of “looking closer” in three ways:

through contemplative criticism (I practiced this for many years as a reviewer for Paste, Image, Christianity Today, and many other publications, journals, and websites);

through my own creative writing, fiction and non-fiction (So far, I've surrendered four novels to Random House’s WaterBrook imprint, and a memoir called Through a Screen Darkly published by Regal — and I am earning my MFA in creative writing at Seattle Pacific University);

through teaching and public speaking (I been blessed with opportunities to speak at conferences around the world, and teach workshops and classes on creative writing, film studies, and multi-disciplinary art interpretation).

When I listen to people talk about art, I notice two common responses: a reaction (“I liked it!” or “I didn’t like it”), or an analysis (demonstrations of knowledge about the art and the artist). Both are interesting and valuable. But occasionally I get a response that resonates with something richer than a reaction or an analysis. I hear wisdom.

I want to grow in wisdom. I want to encourage it in others. How does that happen?

In the Gospel of Matthew (chapter 6, verses 22–23), we read, “The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is healthy, your whole body will be full of light, but if your eye is bad, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light in you is darkness, how great is the darkness!”

Something is lost in translation here, and it is vital that we get it back.

A fellow I consider a friend, a mentor, and a favorite poet — Scott Cairns — was the first to explain this to me. This scripture is not referring merely to those two eyes in your head. The ancient Greeks had a word: “nous.” Place your hand at the base of your throat, just above your heart — that’s the nous, the place where the mind and the heart meet. You could call it “the eye of the soul.”

What does the eye of the soul do? The nous does a particular work that the ancient Greeks call “theoria” (θεωρία). Theoria is the act of observing, experiencing, and comprehending with the nous. It involves both the intellect and the spirit. Theoria runs deeper than mere analysis; and it reaches farther than mere feeling. It engages the conscience. It involves leaning into the “still, small voice” of the Holy Spirit within us. It involves a weighing of what we know and what we do not know. The nous, through the exercise of theoria, cultivates faith.

I think this is what Jesus is talking about when he tells his strange, subversive stories and then says "Those who have ears to hear, let them hear." When we look and look, and listen and listen, in a spirit of humility and vulnerability, we will be blessed with revelation. What is more, the result of all this close looking and attentive listening will be this: When we look and listen to our neighbors and their creative expressions, we will love them. When we look and listen to the world, we will love the world. Intimately.

I was taught, as a young evangelical, to see my neighbors and the world as an audience upon whom to foist my gospel. This set me automatically in a posture of superiority, of being the one with the answer. It made me look down on their artistic expressions, and it made me presumptuous about my own mediocre inventions. But Christ has called us to set ourselves in a posture of humility and service, and in doing so we will imitate the way he loves us. When we do, God will do a work mysterious work in both the servant and the one being served.

This is true in the endeavor that we call art as well.

It is impossible to exercise theoria without humility, for theoria is about opening ourselves to receive something we cannot explain or know. It is impossible for theoria to be mistaken for emotionalism, because it requires the application of the intellect, and it maintains a healthy distrust of emotions (which are fickle and easily misguided). Theoria is a work of collaborative contemplation, requiring deep attention over time, the acknowledgement that we can never arrive at a final judgment of an experience, and the expectation that there is always more to be discovered and revealed.

When I discovered the words nous and theoria, I realized that they name the sensibility and the activity within which I have enjoyed the most rewarding and transformative experiences of my life.

Let’s look closer together — in the presence of art, in the presence of glory — with the eyes of our souls. Let's contemplate, enjoy, and learn from what we find in front of us today.

*

"There was an asterisk at the top of the page. What’s up with the ‘F’ word?"

Yes, I said that I write about faith.

I believe in the person and teachings of Jesus Christ. And I can affirm with deep conviction the claims of the Nicene Creed (which — and I love this fact — is one of the things Stephen Colbert recites to warm up his audience before a show).

As a result, I find myself more at home in the world of the arts than in the hostile and nationalistic distortion of Christianity that is routinely misrepresenting and harming Christ's Gospel in American culture.

For what it’s worth, I’ll say this to address the very valid concerns of many who have been hurt by professing Christians:

I affirm the sacred worth and dignity of all people. God loves all of God’s children unconditionally, and if my behavior does not make it abundantly clear that I am learning to do that too, then I am failing. Contrary to what we see in popular “evangelical” politics, I believe that when the Scriptures command me to “love my neighbor.” And that means I am responsible to not only respect and serve all people, but I am to love them with enthusiasm and respect. This includes immigrants, refugees, all of my BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ neighbors. And thank God for that, because I learn so much from them! While my church/private-school upbringing conditioned me to fear those who do not look like me, talk like me, or conform to the strict sexual codes of most white conservative Protestants, I find that my faith in Christ is routinely enhanced by the testimonies and grace of my diverse community. The Gospel is not exclusionary. The work of Jesus Christ is a reconciliation of all souls within the kingdom of God — and not in some faraway spiritual realm, but here, now, on this earth that is being made new by God’s love.

If you have been betrayed or abused by those of us who claim the name of Christ, I am so sorry. If my heart is ever heavy, that heaviness comes, most likely, from the reality of the suffering inflicted by those who commit harm under the guide of religious piety. When, in weakness and wrongdoing, we who praise the name of Jesus harm you — or anyone — we are also wounding the very God we claim to serve. And I pray that in my writing, I am reflecting the light of God’s unconditional love instead of interrupting how it shines freely and abundantly for us all.

You too can Ghost your readers.

That is to say, you can build a site like this one. I moved to Ghost because I found their methods more admirable and ethical than what I experienced on other platforms.